Our professional associations diluted the research value further by putting more and more people in each session with 5-6 presentations and 1-2 discussants, the better to drive up association membership. While great for association coffers, this leaves less and less time for presentation and discussion. Indeed, panels increasingly feel like “academic speed dating” as each presenter zooms through the presentation hitting the highest points of the chorus, but leaving the gems of the lyrics in the paper, which probably wasn't uploaded to the conference webpage, and is likely to go unnoticed if it is.

With this as backdrop we began to search for things we might do to step into the breach. The current process was created back in the days when academics traveled by train, produced copies of their working papers by having a human being type two copies (an original and a carbon copy) at a time, and then paid the postal service to carry it in a stamped envelope to potential readers. Telephone calls were prohibitively expensive, so it made economic sense for researchers to coordinate annually over a several day period when they could travel to a common location and respond to one another's ongoing work. That we would continue this as our best practice today is an exemplar of path dependent collective stupidity. It doesn’t need to be our grandparents’ 1950’s politico-social. Surely we can do better.

The Past as Prologue

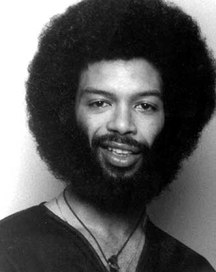

Given our intellectual background, it made sense that our discussions invariably led to a conversation of Charles (Chuck) Tilly (who had recently passed at the time of the conversation referenced above). Chuck had run a workshop at Michigan, the New School and then Colombia that followed some basic rules. Upon being asked about exactly what was involved, these were outlined below by Roy Licklider – a constant participant when the workshop was in New York:

I think we all agree that the seminar/workshop that Chuck created and ran was a remarkable phenomenon. It might be useful to compile its rules in the hope that they might be helpful to others trying to do similar things. Of course, the rules were never written down, and one of the issues with unwritten constitutions is that people often disagree about their content (unlike, say, written constitutions, but that's another story).

Anyway, I thought I would put down my version, and everybody else can explain where I got it wrong. I've put brackets around my comments and specific illustrations from my own experience.

The overriding purpose is to improve a piece of research. Critics are not supposed to show how smart they are by humiliating the author [there was no point to it anyway since Tilly was smarter than anyone else in the room]. A good comment doesn't just point out a weakness in the project; it also suggests what should be done to make it better (constructive criticism).

There is no overriding topic or theme. Basically it is all about how to do good social science research. [The final title was Workshop in Contentious Politics, and there isn't much that couldn't be included under that heading. The lack of a topic made it different from most other seminars and, especially at Columbia, made it difficult to attract members who would keep coming back; Tilly's reputation helped a lot, and some of us became infatuated with the whole approach, but as noted below this became a problem.]

Within the seminar everyone is treated as an equal. First names are used by everyone for everyone. Everyone is an author and a critic; every regular member of the seminar is expected to present (ideally once a year, although that may not be possible) and to comment on everyone else's work every week. Specialized knowledge on the topic is useful but not necessary, and often the best comments and questions come from people who know nothing at all about the topic.

Papers are never presented; they are written and distributed a week ahead of the session. There is a reciprocal arrangement; authors limit themselves to fifty pages or less, and all members read the papers in advance. [Chuck once said it was okay if you didn't read the paper, but you couldn't say so and then make a comment.] The paper should include an introductory page putting the research in context and explaining its audience (is this a dissertation, a potential article or book, a conference paper, etc.).

At the beginning of the session the author is allowed but not encouraged to say a few sentences, usually about the context of the research (which should be covered in the introductory page but sometimes isn't). But the session really starts with extensive comments by two preselected critics, at least one of whom does not have a Ph.D. [In recent years these comments were often written in advance and read aloud, with a copy going to the author either before (my preference) or after the oral presentation. This allows the author to not have to worry about taking notes and facilitates discussion. Chuck and I disagreed about reading the comments; I felt that, at least for native speakers of English, people should talk about the comments rather than reading them, which would be good practice for conferences and teaching classes.]

After the two critics have made their remarks, the author is given a substantial amount of time to respond.

The floor is then open to comments and questions. Members attract the attention of the leader by raising their hand (one-finger question); the leader keeps a queue of names and calls on them in the order in which they have been seen, except that the first three comments after the critics must be made by people without Ph.D.s. It's okay for an individual to raise several separate questions at once. A second kind of intervention is the two-finger question--it must be directly on the point under discussion and thirty seconds or less. Asking a two-finger question does not change your position in the regular queue.

In addition to oral comments, members are encouraged to submit written comments. These fulfill at least two different functions: (1) they communicate specialized knowledge, bibliography, etc. which would not be of general interest to the group and (2) by repeating the oral questions or points, they again free the author from trying to take notes while answering a barrage of very different questions and issues and give them a record of the discussion which will be useful later when trying to recall what went on. [I have actually tape recorded several sessions where I was the author for the same reason. I learned from Chuck to try to keep my own comments until late in the session; with any luck others would make the points on their own and learn more from the experience than if we led the discussion.] Repeating a point made earlier, it is a firm rule that, no matter how wrong-headed the paper is [and there were some dillies], discussion is courteous, friendly, respectful, and directed at improving the project at hand rather than showing that the commentator is brilliant or that the author is insane or dangerous (although all of these may be true). Ideally the author is presented with several different ways in which the paper can be further developed, often contradictory ones which gave some choice.

After the seminar (which is scheduled for two hours), everyone is invited to go out to dinner somewhere nearby (it obviously helps if the seminar is scheduled late in the afternoon). The check is shared, but the author doesn't pay. [I used to explain that they had provided the entertainment. This may not be haute cuisine; Chuck would alternate between two inexpensive restaurants (usually ethnic). He justified this by saying he wanted to encourage graduate students to come by keeping it cheap. When he didn't attend during the last semester, the seminar went somewhere else to eat, although not to a much more expensive place, so maybe he was on to something. Once, when only faculty showed up, we went to a better restaurant. Occasionally, if he had gotten a nice check (as he would put it), he would pay the whole bill himself.

I think he regarded the dinner as the high point of the experience, and certainly many of us did. I made a point not to sit next to him to give graduate students a shot at him; at Columbia they were sometimes a little shy, but they soon got over it.]

With Chuck's Workshop in mind, three years ago we decided to create something in line with the spirit outlined above but do it virtually, online – taking the older model into the 21st Century. The Conflict Consortium Virtual Workshop was born.

Challenges & Successes: Our Experience to Date

Given where we were coming from, we anticipated that there might be some issues to overcome.

For example, who the heck would want to put themselves through what some view as a grueling performance of academic “Survivor,” which is one thing in a room of 5-50 people who after leaving the room basically forget the whole experience. This is quite a different matter when half a dozen people have 90 minutes to discuss your working paper, live on the Internet, and the whole thing is recorded to CC's YouTube Channel for posterity. Have you been to a panel where a discussant rips into the presenter and the audience (seeing the “blood in the water”) moves in for a kill like some version of “Academics Gone Wilding”?

In contrast, we wanted to “nurture the youth,” and limited CCVW applications to working papers by non-tenured faculty and PhD students. We were interested in getting people comments on their work and doing this in the supportive way that Chuck had managed to pull off. We began by adopting Chuck's “Rules of Engagement” (as articulated by Licklider), bounced back and forth drafts of carefully worded emails and a blog post, shared our vision face to face with senior folks we know play well with non-senior folks, and selected kind, engaging and communicative participants to serve as Discussants. We also continued to remind one another to keep a watchful eye on interactions while sessions are underway, task the Chair (one of us) with mediating (should the need arise), and hold a dyadic debrief after each session to discuss how we might improve. Without exception all of these interactions have, indeed, been marvelous.

That said, we have not been deluged with applications in response to our Calls for Papers, and as such, are still working on getting the word out. The CCVW provides a unique opportunity: where else can one get half a dozen conflict researchers to spend 90 minutes giving you feedback on your working paper? We have discussed collecting testimonials, and we ask our past participants to spread the word virtually and face-to-face. As with any new endeavor, however, progress can be a bit plodding and we can always get more assistance in moving things forward (did we mention that we were being backed by the NSF?).

Another potential challenge concerned soliciting free labor: who would be willing to sit and participate 1½ hours to discuss someone else’s work (we very consciously try to build networks by selecting participants who do not know one another well, but given the small size of the community our success varies).

Here, too, Chuck inspired us. He enjoyed speaking and was an incredibly good as well as entertaining speaker. But, one thing that stood out to us about Chuck (and many other, given the tributes written after he had passed) was his desire to help people do better social science. Davenport, who was able to participate in several Workshop sessions over the years, gained tremendously from his interactions with Chuck. Davenport came to realize that Chuck would never really tell you what he thought was the most promising approach. Rather, he would provide 2-3 alternative ways that seemed equally promising. Now, his opinion might have existed somewhere in the three (like some intellectual shell game) but Davenport never found the shell that contained the item he preferred. Always teaching, Chuck knew better than to just hand one a solution. With that approach he engaged researcher's work and joined them in their search to find the right argument, the right data, the right test or the right conclusion. He truly enjoyed the journey and as we would find, many of us similarly enjoyed it as well.

To our delight we have found the people in the conflict and peace community remarkably gracious with their time and supportive of the endeavor. Plenty of people are unable to accept a specific invitation due to a travel or other commitment, but with the exception of a few “non-responses” we have people not only willing, but enthusiastic to contribute time reading the paper and then an hour and a half online in discussion.

Equally important, if you watch some of the sessions we are sure you will agree that the quality of comments, suggestions, and discussion are very high quality: much stronger than the type of exchange we tend to generate at out megameetings. This has been, perhaps, the most gratifying part of the experience for us.

Third, might 90 minutes be too long? Given the short amount of time that most academics get to discuss their work, we wondered if we could provide an environment where actual conversations could emerge – online, among strangers.

Scheduling the sessions for 1½ hours proved a good decision. The conversations are engaging, content-rich, insightful, occasionally funny and quite useful – not just for the presenter but for all that observe the interaction. Individuals come away with a sense of how the presenter as well as other participants think but also how one responds, how research designs are structured, how data is collected and how results are written - all of the components of a decent research paper.

The conversations also seem to have an interesting rhythm to them. The beginning typically leads to partial immersion, followed by a bit of a lull, then a deeper dive to full immersion, some reflection, some probing, and then at about the hour mark there is often something of a 7th inning stretch, after which the full energy returns for the final twenty five minutes, and we almost always ending up cutting off the conversation due to time rather than having it “run out of steam.”

We have also encountered the standard sorts of diversity that confront science. In an October 2013 blog post, Moore lamented a particularly lopsided gender session, and reviewed the numbers to date. Our process has become one where Moore takes the lead generating a list of six people to invite as Discussants and a list of four to six “alternates” to pursue as we get declines. Davenport then reviews, and revises the list. Given that the two of us, who are male, participate, we have found that four women and two men in our initial six works best for striking a gender balance. We also try to get at least one full Professor and two other tenured faculty, filling out the roster with Assistant profs and PhD students. We also like to find at least one person who is from a different field (generally Economics, Sociology or Psychology). And we want our panel of discussants to represent different subfields, research networks, and so on. Did we mention race? Language? The global south? The fact that the time of day systematically excludes Asia is an issue as well (which is asleep at the time of our e-event)?

That sounds like a fun set of dimensions to maximize, right? Needless to say, we do not maximize that multi-dimensional space. Instead, we start with a list of names, eyeball our criteria, and start cutting and adding, cutting, and adding people (sometimes searching our CC Member List, Google Scholar, References of papers, and so on). It is a very seat-of-the-pants (or skirt) process, and hopefully we haven't sucked at it.

To CCVW and Beyond!

With two year's experience under our belt we are pleased with where the CCVW is. And we have begun to seek out other uses for the virtual format. One extension concerns what we call “Data Features.” Deviating from the standard workshop, these will involve a short data presentation, but immediately afterwards we will open the “floor” for an invited panel to ask questions about how the data were collected, what could be done with it, what has been done with it and what would they have done differently or next.

Another extension acknowledges that megaconference panels that actually “work” are frequently just too brief, and that there is really no reason why we could not continue these conversations off-site and online. We are calling these “Conflict Consortium Continua” as the presentations and conversations should be thought of as moving along a continuum of interaction. We will be adding these to the mix over the next year. We also discuss additional extensions, and welcome your ideas and feedback.

Please Steal this Idea

In closing, we hope that others will follow our lead, launch virtual workshops for their communities, and produce even better innovative public goods for nurturing research. Indeed, the Legislative Studies Virtual Workshop and Virtual IPES are already up and running. The International Methods Colloquium offers another model. Some will want to invest their energy in changing the existing megaconferences, and there is nothing wrong with that (basically). This said, we hope to see more entrepreneurs thinking of novel ways to leverage communications technologies in the service of the production of scientific knowledge. As the voice-over for old tv show The Six Million Dollar Man so presciently reminded us, “We have the technology.” Now it is time to use it.

This post is cross-posted at Analog (the anti-blog) and Will Opines.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed