Teaching

Albert Pike — "What we do for ourselves dies with us. What we do for others and the world remains and is immortal."

James Carse -- “To be prepared against surprise is to be trained. To be prepared for surprise is to be educated.”

I love to teach. As Pike tells us, it is a way of sharing, of becoming part of the grand conversation. If done right, it facilitates thought, growth, justice, freedom and enlightenment. Not only for the student but the teacher. Indeed, if done really well (as Carse suggests), the two swap roles throughout the interaction with the student becoming the teacher and the teacher becoming the student, moving the collective (the class) forward to something that could not have existed without either participant and without every step taken along the path.

To date, almost all of my teaching and interaction with students has followed directly from my research. At both the undergraduate and graduate levels, I have taught courses on diverse aspects of political conflict/violence (e.g., human rights violation, genocide, civil war and political dissent): its definition, causes, dynamics, termination, and, recently, its aftereffects as well as coverage throughout diverse aspects of popular culture and collective memory. I have also done

classes on racism and transitional justice. Within these classes, I have endeavored to provide students with a state-of-the-art understanding of what we know as well as what problems remain. In general, my approach is Socratic in nature and as for a general orientation towards teaching I am a strong advocate of John Dewey’s work – especially that articulated in Democracy and Education, as well as that of Rom Harre.

Directly related to the statements and individuals above, I have facilitated diverse environments in which students can further advance their understanding of relevant phenomena.

For example, one of the first things that I did was create a research study group of individuals interested in practical applications of diverse research methodologies (e.g., time series statistical techniques and computer simulation). Within the class/workshop, I led discussions based on assigned readings and spent numerous hours working with the students through specific programs and research materials.

In addition to this, based off of a similar model created by Charles Tilly at Colombia University, at each institution I have been employed, I consistently created and managed (along with several other faculty) a workshop on conflict, violence and (less frequently) peace. These workshops are dedicated to engaging those interested in the topic from a wide variety of perspectives through a rigorous process of critique and discussion. With Will Moore, I then took this format online with the Conflict Consortium's VIrtual Workshop.

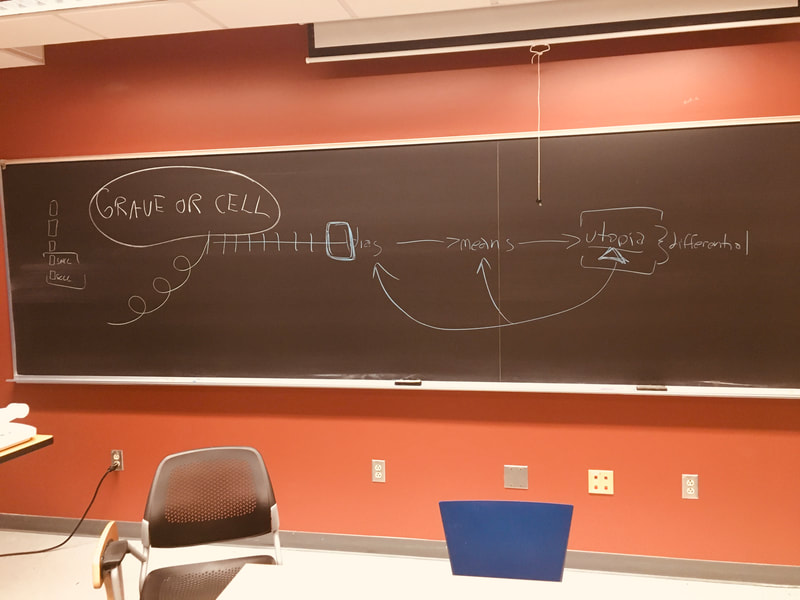

Within my undergraduate classes, I tend to introduce simulation and role-playing as an important mechanism of instruction. For example, I created a game called “Power to the People” which compels students to adopt positions of social movement and political authority – respectively trying to bring about social change or prompt the existing socio-political order. At the graduate level, I tend to focus more on student presentations (based off of a computer simulation technique called Stella II), group discussions and focused debates about diverse topics. This maintains the high level of interaction found in the undergraduate environment but sustains a more sophisticated level of exchange.

Finally, I have also assisted numerous students through the development of special research methods classes as well as directed readings and by directly incorporating them into on-going research efforts. For example, one former student that I had in a comparative human rights class later was employed as a research assistant on my Rwandan political violence project (www.genodynamics.com). She proved to be so essential that I sent her to Rwanda on several occasions to manage data collection and archival efforts. These experiences allowed her to get into the graduate program in political science. This is simply one of many examples. Two other students were also employed on the Rwanda project and a Minorities at Risk class that I ran at one point, when I was running the Minorities at Risk Project. These experiences prompted both to continue their education, leading them both to the London School of Economics. I was so impressed by another student (whose senior thesis I directed) that I contacted a friend of mine at the World Food Program in the Rome office and got her a job, which she took before going to graduate school. I continue in this manner currently employing several undergraduates to work on a project on Northern Ireland and India.

James Carse -- “To be prepared against surprise is to be trained. To be prepared for surprise is to be educated.”

I love to teach. As Pike tells us, it is a way of sharing, of becoming part of the grand conversation. If done right, it facilitates thought, growth, justice, freedom and enlightenment. Not only for the student but the teacher. Indeed, if done really well (as Carse suggests), the two swap roles throughout the interaction with the student becoming the teacher and the teacher becoming the student, moving the collective (the class) forward to something that could not have existed without either participant and without every step taken along the path.

To date, almost all of my teaching and interaction with students has followed directly from my research. At both the undergraduate and graduate levels, I have taught courses on diverse aspects of political conflict/violence (e.g., human rights violation, genocide, civil war and political dissent): its definition, causes, dynamics, termination, and, recently, its aftereffects as well as coverage throughout diverse aspects of popular culture and collective memory. I have also done

classes on racism and transitional justice. Within these classes, I have endeavored to provide students with a state-of-the-art understanding of what we know as well as what problems remain. In general, my approach is Socratic in nature and as for a general orientation towards teaching I am a strong advocate of John Dewey’s work – especially that articulated in Democracy and Education, as well as that of Rom Harre.

Directly related to the statements and individuals above, I have facilitated diverse environments in which students can further advance their understanding of relevant phenomena.

For example, one of the first things that I did was create a research study group of individuals interested in practical applications of diverse research methodologies (e.g., time series statistical techniques and computer simulation). Within the class/workshop, I led discussions based on assigned readings and spent numerous hours working with the students through specific programs and research materials.

In addition to this, based off of a similar model created by Charles Tilly at Colombia University, at each institution I have been employed, I consistently created and managed (along with several other faculty) a workshop on conflict, violence and (less frequently) peace. These workshops are dedicated to engaging those interested in the topic from a wide variety of perspectives through a rigorous process of critique and discussion. With Will Moore, I then took this format online with the Conflict Consortium's VIrtual Workshop.

Within my undergraduate classes, I tend to introduce simulation and role-playing as an important mechanism of instruction. For example, I created a game called “Power to the People” which compels students to adopt positions of social movement and political authority – respectively trying to bring about social change or prompt the existing socio-political order. At the graduate level, I tend to focus more on student presentations (based off of a computer simulation technique called Stella II), group discussions and focused debates about diverse topics. This maintains the high level of interaction found in the undergraduate environment but sustains a more sophisticated level of exchange.

Finally, I have also assisted numerous students through the development of special research methods classes as well as directed readings and by directly incorporating them into on-going research efforts. For example, one former student that I had in a comparative human rights class later was employed as a research assistant on my Rwandan political violence project (www.genodynamics.com). She proved to be so essential that I sent her to Rwanda on several occasions to manage data collection and archival efforts. These experiences allowed her to get into the graduate program in political science. This is simply one of many examples. Two other students were also employed on the Rwanda project and a Minorities at Risk class that I ran at one point, when I was running the Minorities at Risk Project. These experiences prompted both to continue their education, leading them both to the London School of Economics. I was so impressed by another student (whose senior thesis I directed) that I contacted a friend of mine at the World Food Program in the Rome office and got her a job, which she took before going to graduate school. I continue in this manner currently employing several undergraduates to work on a project on Northern Ireland and India.

The Art of Domination and Resistance

(with Dan Slater)

Syllabi link

Saving the World or Wasting Time? Understanding Social Movement Efficacy

Police Violence

The Laws of Change

Domination, Resistance and Back Again:

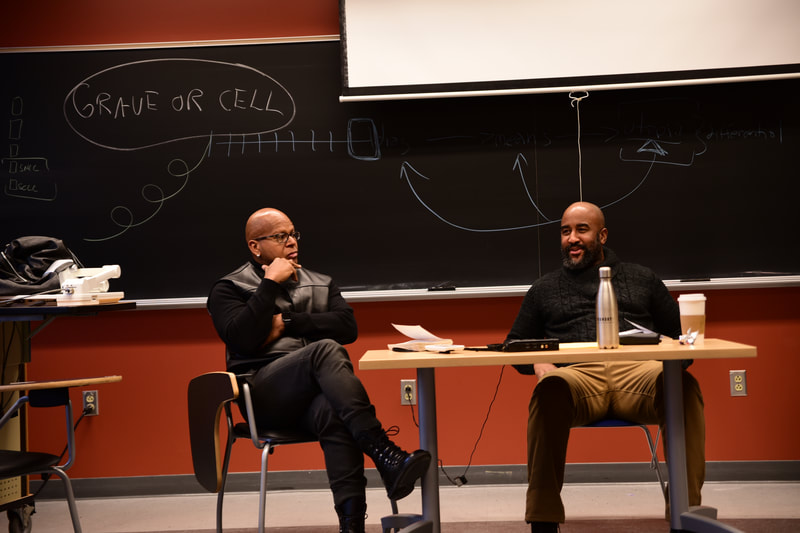

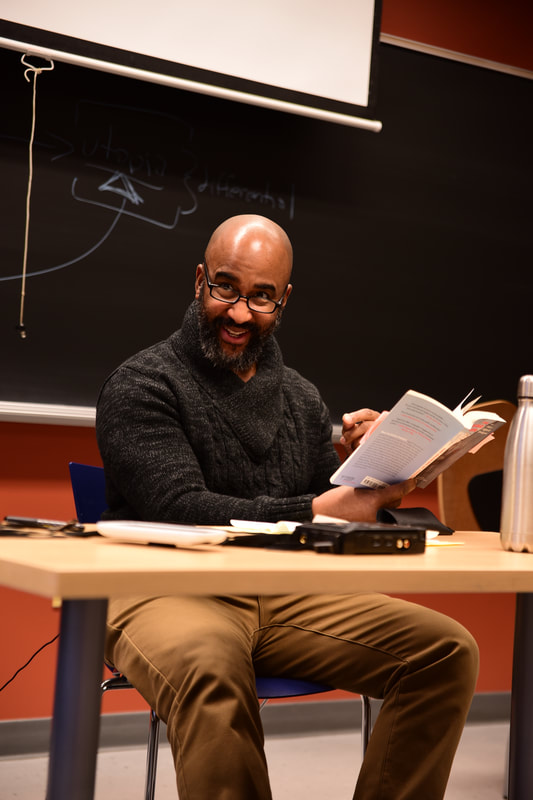

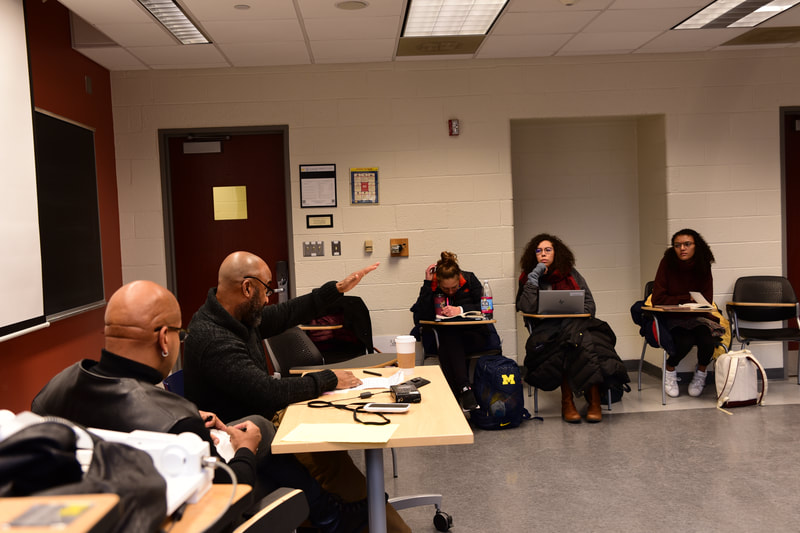

The James Scott Retrospective (2020)

Syllabi: Domination, Resistance and Back Again: The James Scott Retrospective

From the Syllabi: The class will try to locate Professor James Scott in some multi-dimensional space that is "contentious politics". With these parameters, the idea is to trace Prof. Scott’s evolution over time. We will do this in order to understand:

- contention (why does it exist, why does it take the forms that it does, how does it function, what does it do/what doesn’t it do);

- to understand Prof. Scott (where did he start, what tools has he used/why, how did he employ these tools, what insights were garnered, where are the limitations with the work, how did the next piece address/leave those limitations and where are we left in the end regarding our understanding of how we should think about contentious politics); as well as

- to understand ourselves (i.e., how each of us as researchers should and do study the topic relative to the first two topics).

The class and experience should be amazing. I have loved reading each of Prof. Scott’s books with often many years between each reading - the notes I have throughout the books are incredibly extensive and they have led to a great many ideas (some of which I pursued but most of which I have not). Reading much of Prof. Scott’s work should be exciting.

Below, I include several of the final projects that were generated.

Amytess Girgis

Concerning Us:

Stories of Organizing, Resistance, and Resilience

Pilot Podcast Episode (Link Below)

The core of James Scott’s theory on resistance is comprised of the back-and-forth between hidden and public, illegible and legible, infra-political and political. But what happens when moments in history demand we attempt to bridge the gap between these disparate worlds? How can subordinates hope to manipulate these tensions in a way that benefits the oppressed?

In studying resistance stories of the past, subordinates are able to accumulate specialized knowledge over time. In archiving stories of the present, they are able to protect a narrative of resistance free from institutional cooptation. Though the precipice between “storytelling” and “cooptation” will always be steep, this project aims to use Scott’s writing to inform work which straddles these two worlds as effectively as possible.

“Every subordinate group creates, out of its ordeal, a ‘hidden transcript’ that represents a critique of power spoken behind the back of the dominant…relations of domination are at the same time relations of resistance” James Scott, Domination and the Arts of Resistance, xii;45

Beginning at the 24:39 mark, Hoai An tells the story of when she helped organize the “Stop Spencer” campaign. When Richard Spencer attempted to come to U-M’s campus in 2018, she delved into Ann Arbor’s archives to learn that there had been a nearly 20-year period in the late 20th century in which Nazi-sympathizers demonstrated in Ann Arbor. By looking over responses to those protests, she was able replicate tactics used by anarchist organizers back then as well as accurately predict the response of the public and law enforcement. Hoai An emphasizes that white supremacists are excellent at passing knowledge down from one generation to the next; leftist organizers are not, but if we seek to resist effectively and sustainably, we must be. Archiving is a critical step in this work – not only does it force the archiver to contextualize the present with the movements of the past, but it provides a framework by which future organizers can better understand the tactics we use today.

Yet there exists an implicit tension in publicly archiving decentralized organizing. Much of the resistance work we aim to highlight is community-based resilience work – indeed, work that exists either as a juxtaposition to state legitimacy or outside the state framework entirely. Mutual aid, water provision, quiet prison protests – all of these are infrapolitical acts of resistance which succeed because they keep the hidden transcript hidden (and only partially exposed when needed). Yet in some cases, leverage for change is up for the taking. If the hidden transcript is too fully hidden, and for too long, the subordinate class loses leverage entirely because public pressure does not exist to mitigate the damage of the public-facing obstacle. Effective outward-facing archiving, then, must occasionally lift certain voices and phrases in order to legitimize the endeavor to mainstream dominants; but it cannot do so at the cost of losing invaluable hidden transcript of the subordinates.

“Enumerate the parts of a carriage. Still not a carriage.” – Chinese Proverb shared by Prof. Scott to Prof. Davenport’s Class

Starting at the 11:45 mark, Amytess and Hoai An talk about the irreplaceable benefits of deeply understanding the community in which one organizes. Decentralized, community-based organizing cannot occur with a template, but must be built over time based on relationship-building and accumulated knowledge of community characteristics and needs. This knowledge must not only be accumulated in an individual’s lifetime but must also be communicated to their peers as well as to future generations.

In Seeing Like A State, Scott emphasizes that métis by definition is almost illegible to the grid-like nature of state imposition. This includes record-keeping and history-writing. Because métis is so rooted in situational knowledge, its work is not as easily documented as the progress reports of government projects or the record-keeping of nonprofits organizations. But, as Hoai An discusses in the Stop Spencer case outlined above, archiving this type of work is critical for building sustainable movements – particularly when those movements are combatting the power of institutional legitimacy.

Stories of Organizing, Resistance, and Resilience

Pilot Podcast Episode (Link Below)

The core of James Scott’s theory on resistance is comprised of the back-and-forth between hidden and public, illegible and legible, infra-political and political. But what happens when moments in history demand we attempt to bridge the gap between these disparate worlds? How can subordinates hope to manipulate these tensions in a way that benefits the oppressed?

In studying resistance stories of the past, subordinates are able to accumulate specialized knowledge over time. In archiving stories of the present, they are able to protect a narrative of resistance free from institutional cooptation. Though the precipice between “storytelling” and “cooptation” will always be steep, this project aims to use Scott’s writing to inform work which straddles these two worlds as effectively as possible.

- Outward-Facing Archiving: Tension Between Hidden and Public Transcript

“Every subordinate group creates, out of its ordeal, a ‘hidden transcript’ that represents a critique of power spoken behind the back of the dominant…relations of domination are at the same time relations of resistance” James Scott, Domination and the Arts of Resistance, xii;45

Beginning at the 24:39 mark, Hoai An tells the story of when she helped organize the “Stop Spencer” campaign. When Richard Spencer attempted to come to U-M’s campus in 2018, she delved into Ann Arbor’s archives to learn that there had been a nearly 20-year period in the late 20th century in which Nazi-sympathizers demonstrated in Ann Arbor. By looking over responses to those protests, she was able replicate tactics used by anarchist organizers back then as well as accurately predict the response of the public and law enforcement. Hoai An emphasizes that white supremacists are excellent at passing knowledge down from one generation to the next; leftist organizers are not, but if we seek to resist effectively and sustainably, we must be. Archiving is a critical step in this work – not only does it force the archiver to contextualize the present with the movements of the past, but it provides a framework by which future organizers can better understand the tactics we use today.

Yet there exists an implicit tension in publicly archiving decentralized organizing. Much of the resistance work we aim to highlight is community-based resilience work – indeed, work that exists either as a juxtaposition to state legitimacy or outside the state framework entirely. Mutual aid, water provision, quiet prison protests – all of these are infrapolitical acts of resistance which succeed because they keep the hidden transcript hidden (and only partially exposed when needed). Yet in some cases, leverage for change is up for the taking. If the hidden transcript is too fully hidden, and for too long, the subordinate class loses leverage entirely because public pressure does not exist to mitigate the damage of the public-facing obstacle. Effective outward-facing archiving, then, must occasionally lift certain voices and phrases in order to legitimize the endeavor to mainstream dominants; but it cannot do so at the cost of losing invaluable hidden transcript of the subordinates.

- Inward-Facing Archiving: Preserving Métis

“Enumerate the parts of a carriage. Still not a carriage.” – Chinese Proverb shared by Prof. Scott to Prof. Davenport’s Class

Starting at the 11:45 mark, Amytess and Hoai An talk about the irreplaceable benefits of deeply understanding the community in which one organizes. Decentralized, community-based organizing cannot occur with a template, but must be built over time based on relationship-building and accumulated knowledge of community characteristics and needs. This knowledge must not only be accumulated in an individual’s lifetime but must also be communicated to their peers as well as to future generations.

In Seeing Like A State, Scott emphasizes that métis by definition is almost illegible to the grid-like nature of state imposition. This includes record-keeping and history-writing. Because métis is so rooted in situational knowledge, its work is not as easily documented as the progress reports of government projects or the record-keeping of nonprofits organizations. But, as Hoai An discusses in the Stop Spencer case outlined above, archiving this type of work is critical for building sustainable movements – particularly when those movements are combatting the power of institutional legitimacy.

Anahera Nin

James Scott’s work predominantly focused on this struggle between a dominant group and a subordinate group. In order to immobilize individuals, a social system is put in place where laws or rules are made that are explicitly in the interest of a superficial sort of order. The interactions in the hidden transcript and public transcript are what allow resistance to continue to bubble up offstage and form into everyday resistance. What has interested me the most in Scott’s works is the relationship and interaction between the dominant and the elite, primarily within the realm of the public transcript and the hidden transcript.

In Domination and the Arts of Resistance: Hidden Transcripts (1990), Scott introduces the struggle between the dominant (the powerful) and the subordinate (the less powerful) as well as the hidden and public transcript. Scott argues the need to compare and contrast the hidden transcript and the public transcript which involves evaluating the performances of the dominant and the subordinate in order to make a commentary on society. In Seeing Like a State: How Certain Schemes to Improve the Human Condition Have Failed (1998), we see a social system being exerted onto individuals that worked to simplify and optimize society. However, this was often thwarted by the hidden transcript in the form of metis, illegible and localized knowledge that allowed society to work in the untidy and complex way it does. The Art of Not Being Governed: An Anarchist History of Upland Southeast Asia (2009) saw the introduction of hill people and the idea that if we analyzed the hidden transcript and the public transcript, it proves that people who were labelled as uncivilized were driven out of the state and lived in the valley in order to remain outside of the state. Scott’s final work that we read, Two Cheers for Anarchism: Six Easy Pieces on Autonomy, Dignity, and Meaningful Work and Play (2012), saw the emphasis of the hidden and public transcript of ordinary people, and how it is within the power of ordinary people to make the most meaningful change. It is through practising the anarchist law of calisthenics and breaking small laws through everyday resistance that we allow some of our hidden transcripts to come to light and encourage others to do the same, creating this ripple effect that in hope “acts like a virus” and spreads through society, sparking revolution.

I used the dominant and subordinate relationship to synthesize the thread within Scott’s works that showcases this interplay through the hidden transcript and the public transcript and how this leads to resistance. I wanted to emphasize that this resistance is generally created through the random, everyday actions of ordinary people.

To do this, I created a series of 8 Tiktoks on the social media platform Tiktok that emphasize my argument in terms of the hidden and public transcript in the books and within the current events of today. I decided to use Tiktok because it is the most popular social media platform currently among this generation and so it would be the most effective in communicating Scott’s argument to someone in this generation. For each of my Tiktoks I used a popular Tiktok format and would tailor each video to what I thought would get across my synthesization of Scott’s argument to the youth of today. Four of my Tiktoks were representations of the argument in terms of what we read but I simplified it immensely and tried to convey my argument in a way that this generation could understand in the 15-60 seconds I had of their attention.

In Domination and the Arts of Resistance: Hidden Transcripts (1990), Scott introduces the struggle between the dominant (the powerful) and the subordinate (the less powerful) as well as the hidden and public transcript. Scott argues the need to compare and contrast the hidden transcript and the public transcript which involves evaluating the performances of the dominant and the subordinate in order to make a commentary on society. In Seeing Like a State: How Certain Schemes to Improve the Human Condition Have Failed (1998), we see a social system being exerted onto individuals that worked to simplify and optimize society. However, this was often thwarted by the hidden transcript in the form of metis, illegible and localized knowledge that allowed society to work in the untidy and complex way it does. The Art of Not Being Governed: An Anarchist History of Upland Southeast Asia (2009) saw the introduction of hill people and the idea that if we analyzed the hidden transcript and the public transcript, it proves that people who were labelled as uncivilized were driven out of the state and lived in the valley in order to remain outside of the state. Scott’s final work that we read, Two Cheers for Anarchism: Six Easy Pieces on Autonomy, Dignity, and Meaningful Work and Play (2012), saw the emphasis of the hidden and public transcript of ordinary people, and how it is within the power of ordinary people to make the most meaningful change. It is through practising the anarchist law of calisthenics and breaking small laws through everyday resistance that we allow some of our hidden transcripts to come to light and encourage others to do the same, creating this ripple effect that in hope “acts like a virus” and spreads through society, sparking revolution.

I used the dominant and subordinate relationship to synthesize the thread within Scott’s works that showcases this interplay through the hidden transcript and the public transcript and how this leads to resistance. I wanted to emphasize that this resistance is generally created through the random, everyday actions of ordinary people.

To do this, I created a series of 8 Tiktoks on the social media platform Tiktok that emphasize my argument in terms of the hidden and public transcript in the books and within the current events of today. I decided to use Tiktok because it is the most popular social media platform currently among this generation and so it would be the most effective in communicating Scott’s argument to someone in this generation. For each of my Tiktoks I used a popular Tiktok format and would tailor each video to what I thought would get across my synthesization of Scott’s argument to the youth of today. Four of my Tiktoks were representations of the argument in terms of what we read but I simplified it immensely and tried to convey my argument in a way that this generation could understand in the 15-60 seconds I had of their attention.

- What the subordinates wished they could do #jamesscott #domination #resistance #hiddentranscript” and can be found here: https://www.tiktok.com/@anaheranin/video/6818382510414679301

- “What subordinates actually did #jamesscott #domination #resistance #hiddentranscript #publictranscript” and can be found here: https://www.tiktok.com/@anaheranin/video/6818383783595625734

- “Public Transcript lol #jamesscott #seeinglikeastate #domination #resistance #whatactuallyhappens” and can be found here: https://www.tiktok.com/@anaheranin/video/6818383895751314694

- “Hill People’s Thought Process #jamesscott #theartofnotbeinggoverned #domination #resistance #hiddentranscript” and can be found here:https://www.tiktok.com/@anaheranin/video/6818384094968155398

- “Practicing everyday resistance - this is what my public transcript looks like #jamesscott #twocheersforanarchism #domination #resistance” and can be found here: https://www.tiktok.com/@anaheranin/video/6818384276590005509

- Covid-19 Rich vs Poor #publictranscript #hiddentranscript #covid19 and can be found here: https://www.tiktok.com/@anaheranin/video/6818384617368767749

- “Let’s make the hidden transcript public and expose the state Part 1 #covid19 #domination #resistance” and can be found here: https://www.tiktok.com/@anaheranin/video/6818384758792359174

- Making the hidden transcript public Part 2 #covid19 #donaldtrump #domination #resistance” and can be found here: https://www.tiktok.com/@anaheranin/video/6818386451777064197

- “Let’s make the hidden transcript public Part 3 #covid19 #exposed #domination #resistance” and can be found here: https://www.tiktok.com/@anaheranin/video/6818386597441047813

Elizabeth Compton

The dynamic between dominants—those who hold power in some form over others—and their subordinates is the site of inquiry for much of political scientist and anthropologist James C. Scott’s work. The intent of my project is to both engage with and visually represent Scott’s writings on language’s influence on this dynamic, especially as it is used as a tool in domination—the act of exercising power and its maintenance—and in resistance—efforts by subordinates to evade or push back against such actions—in the public transcript. Each of the four books read by our class provides some treatment of language in relation to domination and resistance, giving particular emphasis to the imposition of a national language as a foundational step in state formation and the maintenance of that national language in continued control. The ability to control language is the ability to control information, as well as “a precondition of many other simplifications” to make a population easier for dominants to administer.1 At the same time, this means that regional, local languages provide a tool for resistance in the audience they delimit. Additionally, the inevitable lies, gaps, and hypocrisies in dominant narratives are ripe for exploitation by subordinates and incorporation into measures of resistance.

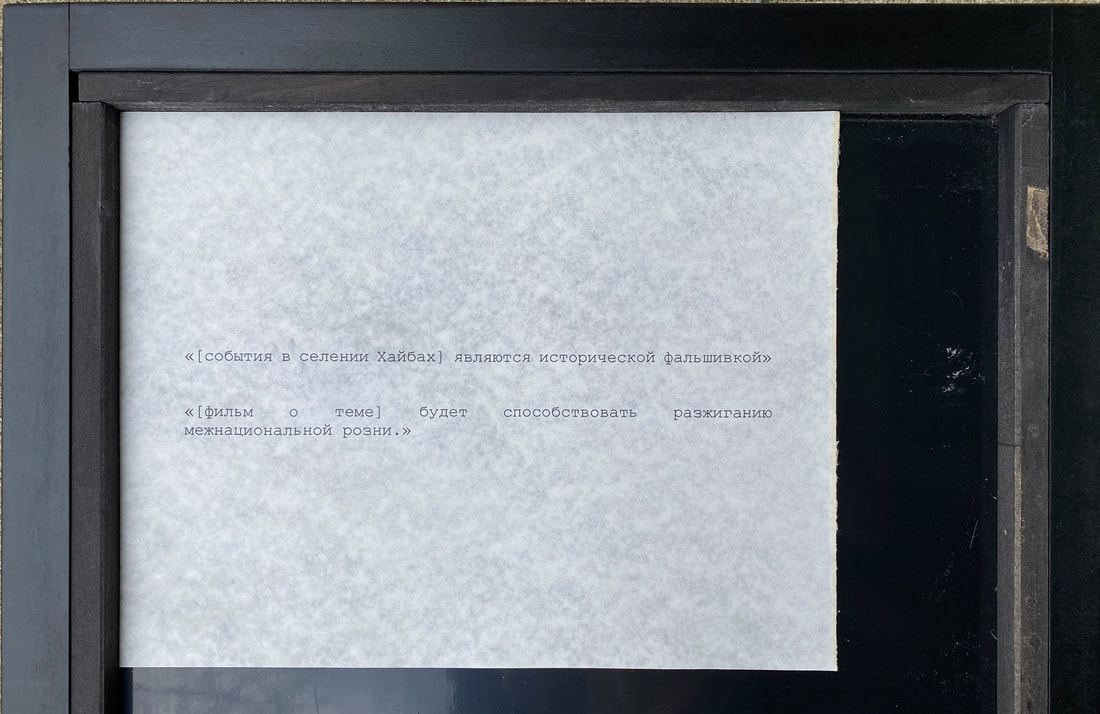

The Khaybakh Massacre is a contested event in Chechen-Russian history, and, as such, a strong example of Scott’s ideas about the powers of language in application. The history of violent struggle between Russian empire and Chechen subject spans centuries, but the 1944 deportation of Chechens from their native land is perhaps the most bitter nadir. Chechens were forcibly removed from their homes, loaded into cattle cars, and driven thousands of miles to Kazakhstan as a collective punishment for the alleged collaboration with Nazi forces.2 Many perished during the journey due to the conditions of the transport, and many were shot and killed before they ever reached the cattle cars if they were uncompliant or simply unable to travel due to their physical condition. In one village, Khaybakh, a handful of witnesses have maintained that hundreds of Chechens were forced into a large barn and burnt alive when the logistics for their removal by transport were deemed too complicated. This event has come to be known as the Khaybakh Massacre and its authenticity remains contested due to few witnesses and little documentation and—above all—the horrific violence it describes. While the Russian state has not only allowed, but, at times, solicited investigation into the historical veracity of the massacre, a recent official stance (represented in the top panel in the project) claims the events there did not constitute a massacre and the story of the mass burning is invented.3 Across most Chechen accounts, regardless of their level of allegiance to the Russian state, the event is considered authentic and often considered representative of the utter horror of the larger national tragedy of the deportation.

The texts selected for this project include four excerpts from narratives presented by individuals occupying differing levels of power in relation to the Russian state, whose quotes were chosen as more or less representative of people at their respective levels of power (one shown here). The four “speakers” included are a Russian state official, an ethnic Russian journal author, a Chechen state official, and a Chechen witness. The three excerpts in Russian and one in Chechen are represented in order of narrative officialdom, with the top panel representing the public, official narrative of the dominant (the Russian state), and the panels below representing increasing distance from that narrative.4 While an argument could certainly be made that the Chechen state official occupies a place of greater power than the ethnic Russian author, the Chechen state official strays more from the narrative of the dominant Russian state. A translation and contextualization for each text has been provided in an additional attachment, and, if I were to properly display the project, these translations would ideally be printed on transparent stickers applied directly to the wall to the right of the corresponding panels.

Taken all together, the design and content of this project are meant to demonstrate the considerable variance possible in the public transcript alone and the competing motivations behind such variance. In designing the project, I made the conscious choice to include all of the panels in one frame to indicate that they are each describing the same event, even if the description denies the existence of the event. During our class discussions with Dr. Scott, he offered the excellent suggestion of aligning the text panels like a body, with those above the waist—particularly at eye-level—representing the most “acceptable” ideas. As Dr. Scott explained, this also subtlety indicates a sort of “talking heads” quality to these acceptable ideas,

The Khaybakh Massacre is a contested event in Chechen-Russian history, and, as such, a strong example of Scott’s ideas about the powers of language in application. The history of violent struggle between Russian empire and Chechen subject spans centuries, but the 1944 deportation of Chechens from their native land is perhaps the most bitter nadir. Chechens were forcibly removed from their homes, loaded into cattle cars, and driven thousands of miles to Kazakhstan as a collective punishment for the alleged collaboration with Nazi forces.2 Many perished during the journey due to the conditions of the transport, and many were shot and killed before they ever reached the cattle cars if they were uncompliant or simply unable to travel due to their physical condition. In one village, Khaybakh, a handful of witnesses have maintained that hundreds of Chechens were forced into a large barn and burnt alive when the logistics for their removal by transport were deemed too complicated. This event has come to be known as the Khaybakh Massacre and its authenticity remains contested due to few witnesses and little documentation and—above all—the horrific violence it describes. While the Russian state has not only allowed, but, at times, solicited investigation into the historical veracity of the massacre, a recent official stance (represented in the top panel in the project) claims the events there did not constitute a massacre and the story of the mass burning is invented.3 Across most Chechen accounts, regardless of their level of allegiance to the Russian state, the event is considered authentic and often considered representative of the utter horror of the larger national tragedy of the deportation.

The texts selected for this project include four excerpts from narratives presented by individuals occupying differing levels of power in relation to the Russian state, whose quotes were chosen as more or less representative of people at their respective levels of power (one shown here). The four “speakers” included are a Russian state official, an ethnic Russian journal author, a Chechen state official, and a Chechen witness. The three excerpts in Russian and one in Chechen are represented in order of narrative officialdom, with the top panel representing the public, official narrative of the dominant (the Russian state), and the panels below representing increasing distance from that narrative.4 While an argument could certainly be made that the Chechen state official occupies a place of greater power than the ethnic Russian author, the Chechen state official strays more from the narrative of the dominant Russian state. A translation and contextualization for each text has been provided in an additional attachment, and, if I were to properly display the project, these translations would ideally be printed on transparent stickers applied directly to the wall to the right of the corresponding panels.

Taken all together, the design and content of this project are meant to demonstrate the considerable variance possible in the public transcript alone and the competing motivations behind such variance. In designing the project, I made the conscious choice to include all of the panels in one frame to indicate that they are each describing the same event, even if the description denies the existence of the event. During our class discussions with Dr. Scott, he offered the excellent suggestion of aligning the text panels like a body, with those above the waist—particularly at eye-level—representing the most “acceptable” ideas. As Dr. Scott explained, this also subtlety indicates a sort of “talking heads” quality to these acceptable ideas,

“[The events in the village of Khaybakh] are a historical falsification.”

“[A film on this topic] will contribute to inciting ethnic hatred.”

Vyacheslav Telnov, director of the cinematography department of the Russian Ministry of Culture1

This series begins with two fragments from a letter written by Vyacheslav Telnov in 2014 to the creators of “Ordered to Forget,” a film which depicts the Khaybakh Massacre, to deny them a permit to show the film, effectively banning it in Russia. While it is possible this event truly did not occur, it is worth unpacking the reasons for denying the event occurred if, in fact, it did. Perhaps most intuitive is the threat a massacre poses to the Russian state’s reputation (as heir to the Soviet Union) and attendant demands for redress possible from Chechens and other ethnic minority groups. As Scott notes, though, particularly dramatic performances by dominants in the public transcript, especially those invoking moral considerations, may also be more to bolster their own conviction in their own purpose and power than to compel submission from subordinates.2 Dominants must have conviction in hierarchy to remain committed to upholding it, so such denials may be just as much for the preservation of that conviction as to guard against potential consequences from subordinates.

“[A film on this topic] will contribute to inciting ethnic hatred.”

Vyacheslav Telnov, director of the cinematography department of the Russian Ministry of Culture1

This series begins with two fragments from a letter written by Vyacheslav Telnov in 2014 to the creators of “Ordered to Forget,” a film which depicts the Khaybakh Massacre, to deny them a permit to show the film, effectively banning it in Russia. While it is possible this event truly did not occur, it is worth unpacking the reasons for denying the event occurred if, in fact, it did. Perhaps most intuitive is the threat a massacre poses to the Russian state’s reputation (as heir to the Soviet Union) and attendant demands for redress possible from Chechens and other ethnic minority groups. As Scott notes, though, particularly dramatic performances by dominants in the public transcript, especially those invoking moral considerations, may also be more to bolster their own conviction in their own purpose and power than to compel submission from subordinates.2 Dominants must have conviction in hierarchy to remain committed to upholding it, so such denials may be just as much for the preservation of that conviction as to guard against potential consequences from subordinates.

Ryan Miller

Given the current situation the world is in right now, it feels appropriate to turn to James Scott’s work to better understand the current state of affairs. Being someone who has struggled with dyslexia and other learning disabilities throughout my life, I figured it would be most helpful to create a physical manifestation of James Scott’s theory on the battle between the hidden and public transcripts. For those who have not been lucky enough to study his work, a physical representation of this battle will hopefully pique other’s interests and will subsequently motivate them to open up one of Scott’s works.

The physical manifestation comes to life in the form of a pendulum wave, which is a phenomenon in which many independent pendulums are measured to an exact length which when swung allows for a hypnotic effect that produces an initial harmonious wave, which is followed by chaotic and unharmonious swings, and then it finishes in the same beautiful wave form in which it started. This display of physics in motion can be used to display the ongoing battle that takes place when the hidden transcripts make an appearance into the public sphere, which turns the once harmonious pattern of dialogue into a form of chaotic exchanges between the ruling class’s transcripts and the transcript of the dominated.

Similar to the way in which the discourses seem quite normal and unscientific in nature, the process needed to make a pendulum wave follows a similar course. While constructing the display, I did not realize until it was time to swing the balls that there was much more to it than just aligning balls in accordance to the length of its string. After a bout of extreme frustration I realized the sheer amount of mathematics that goes into making a harmonious pendulum wave. I found this to be a revelation as it compares to James Scott’s work, which was rather exciting. Similar to the ways in which Scott compares the public performance that groups act out when in the company of their subordinate or boss, such is the case when a slave is speaking to their master in an extremely obedient tone, but the second the master walks out of the room the tone immediately changes to that of disobedience. This form of disobedience is displayed when the pendulums no longer are lined up and are moving in a chaotic manner which is then lined up again to represent the return to the public transcripts once the slave master enters the room again.

The physical manifestation comes to life in the form of a pendulum wave, which is a phenomenon in which many independent pendulums are measured to an exact length which when swung allows for a hypnotic effect that produces an initial harmonious wave, which is followed by chaotic and unharmonious swings, and then it finishes in the same beautiful wave form in which it started. This display of physics in motion can be used to display the ongoing battle that takes place when the hidden transcripts make an appearance into the public sphere, which turns the once harmonious pattern of dialogue into a form of chaotic exchanges between the ruling class’s transcripts and the transcript of the dominated.

Similar to the way in which the discourses seem quite normal and unscientific in nature, the process needed to make a pendulum wave follows a similar course. While constructing the display, I did not realize until it was time to swing the balls that there was much more to it than just aligning balls in accordance to the length of its string. After a bout of extreme frustration I realized the sheer amount of mathematics that goes into making a harmonious pendulum wave. I found this to be a revelation as it compares to James Scott’s work, which was rather exciting. Similar to the ways in which Scott compares the public performance that groups act out when in the company of their subordinate or boss, such is the case when a slave is speaking to their master in an extremely obedient tone, but the second the master walks out of the room the tone immediately changes to that of disobedience. This form of disobedience is displayed when the pendulums no longer are lined up and are moving in a chaotic manner which is then lined up again to represent the return to the public transcripts once the slave master enters the room again.

Black Political Thought (2019-20)

Persons at the bottom of the well, at the other end of the lash/barrel of the gun, who have been subject to diverse forms of domination, exploitation, and human rights abuses have much to teach us about dignity and democracy, peace and conflict, struggle and solidarity. They also have insights to share about the gap between the Enlightenment ideals of freedom, equality, and fraternity and the lived experiences of the colonized, enslaved, and segregated, and on how to pursue radical social and political transformation where injustice, discrimination, and despair remain features of everyday life.

This course will expose students to thinkers such as W. E. B. Du Bois, Marcus Garvey, Claudia Jones, Martin Luther King, Jr., Imari Obadele, and Angela Davis, who provide distinct, contested, and complex diagnoses about the problems of blacks in American and throughout the African Diaspora, as well as prognoses for how they can be overcome.

1) W. E. B. Du Bois, Darkwater: Voices From Within the Veil (Mineola: Dover, 1999)

2) Marcus Garvey, Message to the People: The Course of African Philosophy (Dover: Majority Press, 1919).

3) Claudia Jones, Beyond Containment, ed. Carole Boyce Davies (Oxford: Ayebia Clarke Publishing Limited, 2011)

4) Martin Luther King, Jr., Where Do We Go From Here: Chaos or Community? (Boston: Beacon Press, 2010)

5) Imari Obadele, War in America: The Malcolm X Doctrine (Detroit: Malcolm X Society, 1968)

Foundations of the Black Nation (Detroit: House of Songhay, 1975)

6) Angela Davis, The Meaning of Freedom and Other Difficult Dialogues (San Francisco: City Lights, 2012)

The student of this course will develop a deep historical understanding of what has been articulated before but also will cultivate what constitutes “the new black agenda” for the current period.

This course will expose students to thinkers such as W. E. B. Du Bois, Marcus Garvey, Claudia Jones, Martin Luther King, Jr., Imari Obadele, and Angela Davis, who provide distinct, contested, and complex diagnoses about the problems of blacks in American and throughout the African Diaspora, as well as prognoses for how they can be overcome.

1) W. E. B. Du Bois, Darkwater: Voices From Within the Veil (Mineola: Dover, 1999)

2) Marcus Garvey, Message to the People: The Course of African Philosophy (Dover: Majority Press, 1919).

3) Claudia Jones, Beyond Containment, ed. Carole Boyce Davies (Oxford: Ayebia Clarke Publishing Limited, 2011)

4) Martin Luther King, Jr., Where Do We Go From Here: Chaos or Community? (Boston: Beacon Press, 2010)

5) Imari Obadele, War in America: The Malcolm X Doctrine (Detroit: Malcolm X Society, 1968)

Foundations of the Black Nation (Detroit: House of Songhay, 1975)

6) Angela Davis, The Meaning of Freedom and Other Difficult Dialogues (San Francisco: City Lights, 2012)

The student of this course will develop a deep historical understanding of what has been articulated before but also will cultivate what constitutes “the new black agenda” for the current period.

"Saving the World or Wasting Time"

(2015-2016)

Classes (Select Listing)

Consequences of Contention

Black Political Thought

Political Violence & the United States & Course Materials

Pop Struggle: Repression and Dissent in Popular Culture

Reading for Sept 11

An Organizational Study of Political Conflict and Violence

Disaggregated, Subnational and Microfoundational Conflict Studies

Death by Government

Ending Political Violence

Saving the World or Wasting Time: Understanding the Impact of Social Movements and Activism

States Vs. Challengers

Governments Vs. People

Civil Conflict

Black Power Movements

Advanced State Repression

Perspectives in/on Conflict

Zen & the Art of Political Measurement

Materials (click)

Black Political Thought

Political Violence & the United States & Course Materials

Pop Struggle: Repression and Dissent in Popular Culture

Reading for Sept 11

An Organizational Study of Political Conflict and Violence

Disaggregated, Subnational and Microfoundational Conflict Studies

Death by Government

Ending Political Violence

Saving the World or Wasting Time: Understanding the Impact of Social Movements and Activism

States Vs. Challengers

Governments Vs. People

Civil Conflict

Black Power Movements

Advanced State Repression

Perspectives in/on Conflict

Zen & the Art of Political Measurement

Materials (click)