This is not new or even isolated to this one campus. Like those in the 1960/70s against the War in Vietnam, Imperialism, sexism and racism as well as in the 1980s against Nicaragua, racism (again/still) and Apartheid, which was an embodiment of war (a civil one), imperialism and racism, young people are seemingly poised to step into the realm of "contentious politics" (i.e., political engagement outside of the parameters of mainstream/sanctioned processes as well as with an element of confrontation being involved). The similarities in topics makes sense. Many of the issues identified earlier have persisted over time and thus it has been necessary to fire up the mechanisms of change every now and again (i.e., the Youth). The differences in framing have also been noted previously. As stated in one article about student activism in the 1980s vs. the 1960s:

Many compare the new student activism to the radical politics of the 1960s, but most say the political techniques have changed. Although students listen to the music and wear the clothes of the baby-boom generation, the focus has shifted to effecting positive change rather than simply protesting.

"There are as many students involved in working for change on campus today as there were in the 1960s," says Yale senior Jon H. Ritter, who has been involved in student activism during his four years at Yale. "The difference is that in the 1960s students were calling for everything at once, while students in the 1980s have more specific goals, and work on one issue at a time."

Students today say that the activism of the 1980s, although it attracts less attention than did the protest movements of 20 years ago, is a more effective method of achieving lasting change.

Seeing what we are observing in the world today as well as in the US in particular, it is not so clear that the 1980s were effective and we could probably all agree on the ineffectiveness of the 1960s outside of the creation of some admittedly important programs. This is hard for me to say for I used to mention with pride that activism at my school in the 1980s (Clark University in Wooster [Woo-stah], Mass) had prompted change through divestment but we discovered later that the University had not divested but simply moved the money from a direct to a more indirect route. While seemingly effective, therefore, we kind of blew it. This and a failure to get a controversial tenure decision overturned revealed to many of us that student activism was a very difficult thing.

Should we be optimistic about the current situation? Well, forgive me on this one but no and yes.

On the no - We should not be optimistic because prior student activists have not learned what is effective and this message has not been transferred to subsequent student bodies. What types of issues were being protested about in the 1960s, 1970s, 1930s, 1980s, 1990s, 2000s and 2010s? What tactics were used and which tactics generally worked in the short term as well as the long term across contexts (e.g., public vs. private schools, the Northeast/Midwest/South/West, in bust/boom financial times, in Republican/Democratic environs, in situations with greater/lesser mixed populations on campus or in the surrounding community)? These are the questions we need answered as we try to forge a more effective way forward. Additionally, where is that student activist book or e-book that is distributed to freshmen/freshwomen/newbies that come on campus for the first time, like the "activist student handbook" to inform them of what the local history has been regarding how students got rights, protected them and extended them across distinct domains? Where is the listing of tactics, places, dates and outcomes so that students can assess what has and has not worked? Where is that generational replacement of activists on campus which need to be built yearly as the conveyor belt of students moves through the relevant institutions?

On the yes - We should acknowledge that now/today is a new day and that we can build a better way forward. We can address the questions above on each campus in the US as well as abroad and then we can compile our "activist student handbooks" in one spot so that students as well as faculty can begin the task of trying to figure out what has/has not worked across campuses. This is not completely subversive as the current President of the United States of America has asked for an "Activist Citizenry". He just didn't tell us how to get there but he doesn't need to. We can work this out for ourselves.

Additionally, we can acknowledge that historically there has been some discussion about the fact that prior student activists have generally not been engaged in activities with those from the communities around them. Although this has been the case generally this does not need not be the case. Now, that said, there are some contentious histories between Universities and the towns that they have existed within stretching back to the founding of most Universities in the US. Remember Breaking Away? Remember School Daze? Needless to say, the locals and the students did not see everything eye to eye nor will we in the current situation. There are a wide variety of differences that we need to be attuned to but it is nevertheless possible.

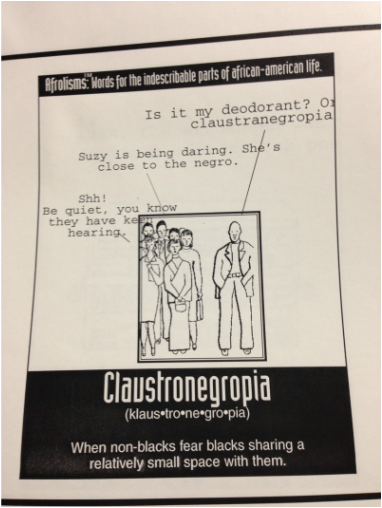

In the current context, we could be especially well primed for such an intersection as we appear to have some momentum addressing anti-black violence and discrimination emerging from different quarters. At the same time, the attention to these issues varies a bit. According to polling data, many whites do not believe that racial problems are that bad whereas many African Americans believe that they are extremely bad. This does not bode well for alliance formation or actual effectiveness but this does not preclude it. To change America - not just the campuses but the broader country - this rift will need to be overcome but this is also where scholarship comes in. People have been working on how differences like those noted above can be overcome. I will follow this piece up with some of that work but feel free to shoot some to me in the meantime.

Now, I would be remiss if I did not mention the fact that we are not working on this in a vacuum. I am sure after the Missouri activism that athletic programs around the US are systematically working to figure out how they can isolate/protect their scholar-athletes from such influences. Those interested in activism, however, need to figure out how such connections can be sustained as well as strengthened. Athletes play an important role in the life of Universities as do non-athletic oriented students, alum, faculty, staff and the communities that surround them. All should be brought together in a manner that facilitates social justice and human rights. This should be the objective. Also, I would be remiss in identifying that social movement activism is great for changing some things but not for others. What is needed is a high degree of monitoring, discussion, analysis and vigilance across the distinct parts of the social change process. (see here and here).

Toward this latter end, I want to suggest a concrete beginning: if you are on a campus in the US, find some willing students as well as faculty and begin a "[insert university name here] activist student handbook". I am currently running a class called "Saving the World or Wasting Time: Understanding the Impact of Social Movements and Activism" (click title for useful reading) and we will begin to to do this for our university starting tuesday (they don't know this yet but I'm sure they will be thrilled). Feel free to join us. Make note of the fact though that Thanksgiving, finals and Christmas break are coming as well as winter for much of the country. Historically, these have not been great times to get students or faculty to focus on social justice issues. We need not be tied to the past however. We can change, no? For example, regarding the upcoming weather, I am reminded of a scene from the Spike Lee film "DROP Squad" (please replace sun and heat with cold and winter as well as forgive the language: click here for relevant scene. Get your hats y'all!

Peace

RSS Feed

RSS Feed