Right off the plane, Mason (not his real name) and I went into a car, immediately blowing by individuals walking along the road, trees and winding hills. Straight we went to what would be my first of perhaps 110 cups of tea that I would have. The reason is clear: 1) its water – which was needed to check hydration, 2) it was boiled – made it relatively more safe. After this I slept for a day or so. When I woke up, I walked around a little; not too much at first.

I had been in Rwanda for about a week before anybody mentioned it. Up to that point I had just been drinking tea (did I mention that), getting used to the climate and meeting individuals from different organizations (the U.S. embassy, Human Rights NGOs and diverse government personnel). We then went to meet our partner institution – the National University of Rwanda in Butare. On the long drive we each just looked out the window on our respective sides of the car, watching the centuries roll back. Upon arriving, we went to our rooms, got unpacked, drank some tea, met some university professors and the Rector – the university president.

That night it came up as four of us sat at the bar: Candace (a white woman that had been in Rwanda for about a year), Mason (my potentially Asian colleague from the university of Maryland) and Frank (a potential white guy who was managing a U.S. AID project) and myself.

Leaning in and lowering his voice, Mason mentioned it first. “Of course, no one talks about it. It’s illegal for goodness sake. When I first came here and asked about it, they just kind of looked at me – offended. There are no differences between us, they told me. We are all Rwandans.”

“Yeah,” Candace jumped in. “Actually, it gets so frustrating. You can see it everywhere. The person you met today was one of them. Actually, there is no one affiliated with our project that isn’t.”

Reluctantly Mason chimed in, “This is particularly annoying because our effort is supposed to help resolve conflict. All we have done is re-establish the same differences that we were attempting to challenge. “

“Um,” I began, “what the hell are you talking about?”

Mason responded, again in a whisper, “ethnicity.”

“Oh,” I continued, “really? But, if no one talks about it, then what do you do? How are you supposed to reference the unreferenceable?”

“Well,” Candace whispered, leaning in, “I have a code that I use.” She leaned closer and halted as the waitress showed up to give us more tea.

As she left, Mason went to the bathroom and Candace continued: “I use Handbags and Teabags.”

“For what?” I asked.

“To discuss the situation… Hutus and Tutsi… the identities of the people we are observing.”

“You’re kidding, right?” I said.

“Nope. For example," Mason continued, "I would say to you that I think the waitress is a handbag or needs to get one. Then you would know what I was saying without them getting upset or knowing what we were talking about. It’ll all come in handy later – believe me. The people I know use it all the time. Things just keep happening here and unless you talk about it, you would just go crazy.”

Handbags and Teabags. What the heck... Ever creative are the outsiders (Mizungus) or, referencing an earlier story - Oh, those crazy mizungus.

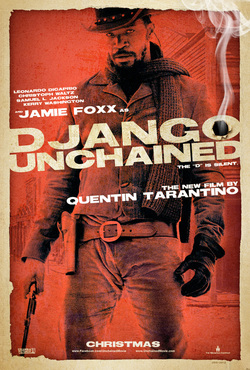

The Handbag and Teabag thing came up frequently as you needed confirmation of the ethical political dynamics. Bank teller? Handbag or Teabag? Farmer? Handbag or Teabag? Military officer, foot soldier, Bank President, craftsman, university administrator? The question is everywhere. It was like navigating the deep south but you could not readily tell who was black or white (except by the position held in society) because everyone looked alike.

For a while, I thought it was like a fairytale thing. For example, if you stuck me in a room with a bunch of African Americans, I could tell who was from the north and south, who had a white relative and perhaps who was confident or insecure as well as their political orientation, hair style, clothes and jewelry. If you stuck the average American in the same room, however, they would not be able to detect any difference; indeed, they might just appear to be a bunch of black folk.

In some contexts, I can even tell when a white person has spent time around blacks and how familiar/intimate that context was – it is all in the body language. Now, the Handbag/Teabag thing was somewhat similar to this because blacks had invented their own language to talk about this stuff and it was not discussed in front of someone else – unless similarly coded.

I thought that maybe I just couldn’t see the difference because I was not from there. I’ll be damned if I didn’t try. Candace couldn’t tell any difference and she had been there for a year. Others confounded this: those there for 5, 10, or 30 years; those that had lived in Rwanda their whole lives; and, those that just came from abroad recently. All saw it but none could name it. This was important not only for understanding who you were talking with and what kind of take they might have on the political violence that took place as well as their opinions about the post-conflict situation. It was also important for understanding the conflict itself. A major part of the conflict involved ethnic tension. If everyone looked the same, however, then how could that be part of the explanation?

As commonly discussed, it is believed that a group of extremist Hutu (members of the Rwandan Armed Forces [FAR], Presidential Guard, national police, the “Zero Network death squads”[i] as well as affiliated militias: the Interahamwe[ii] and Impuzamugambi,[iii]) targeted their ethnic rivals – the Tutsi, and systematically engaged in their abuse and killing. This readily and appropriately led to claims of genocide – the systematic attempt of political authorities in Rwanda to eliminate, in whole or in part, members of an ethnic group and, indeed, some observers referred to the events in question as the clearest example of the concept since the Holocaust. Indeed, the only variation in these discussions was exactly how many people were involved in the bloodshe: some highlighted a small clique whereas others highlighted a large proportion of the Hutu population. But if ethnic identification was so difficult, then how could this explanation be correct? This is especially the case when most of the population was running as refugees/internally displaced. Local knowledge (what many relied upon to identify folks) ain't valid when the whole country is on blast/speed/fast fo(ward).

Other questions abounded as well. For example, if one cannot really tell who somebody is, then are Teabags running things, if no one calls them Teabags? I think so but there is something in not naming a thing. It creates a reality of its own – the nothingness of it all.

In line with this development, we acknowledge that we had no Handbags on the project but knew at some level that without them our work would likely fail. The gaze from our teabag kept us on something of a tight leash. We were led everywhere, introduced to everyone and the only time that I think I saw a handbag in a bookstore, I was watched by our teabag like a child in kindergarten – something that immediately made the unconfirmed handbag uncomfortable and further increased my desire to understand what was going on. In fact, when I asked the guy for some reading material about what happened during the period of violence beyond the “usual stuff,” he took me around the corner and told me I should try to come back to see some readings that he would pull out special for me. Concerned with being watched, he peered around the corner upon spotting my Teabag looking for me, my unconfirmed Handbag shut up and walked back to the front of the store, behind the counter.

I never could get back there without an escort.

The shepherded feeling was immense. It was like: “here is the reality of the situation, don’t bothering looking to the left for there is nothing of importance there. They are there. Looking. Carefully.”

But what kind of reality is it when you are guided through it as in a tower? One might personalize the trip like Philip Gourevitch (the New Yorker author who wrote a highly readable but largely misguided as well as one-sided story about Rwanda) that made it seem like they traveled around the country unescorted, interacting with Handbags and Teabags wherever, whenever and however they wished but this was not the case. The Handbags and Teabags that one saw when they went through Rwanda were perfectly laid out – organized, consistent and symbolic. Prices were clear as were the brands. Locals were all over the store but they weren’t buying it. Their interest lay elsewhere.

[i] This was noted by the study undertaken by the International Panel of Eminent Personalities (57).

[ii] This is the name of the military wing of the National Republican Movement for Democracy and Development.

[iii] This is the name of the military wing of the Coalition for the Defence of the Republic.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed