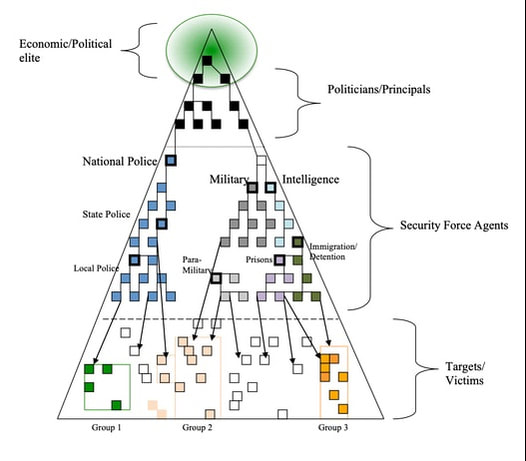

Unlike most research in this area, we did not find that naming/shaming, economic sanctions, signing of international agreements, military intervention and other standard policy options had any consistent/systematic impact on reducing state-sponsored repressive activity. Divestment was not considered because frankly this has not been tried enough times historically. What did have an impact was democratization brought in the wake of some form of civil resistance (mostly non-violent but some that were violent). This influence emerges because we feel that it is only under this circumstance that the cohort of individuals who imagined, ordered and implemented the repressive policy of interest would be removed. Repressive actors do not fear costs and they are not updating in their thinking. Instead, they are doubling down, insulating themselves and going after any/all that criticize them from within and without.

The implication here is important for the current context. If this work identifies a valid approach to stopping an on-going spell of human rights violation, then this would suggest that many of the efforts being put forward to stop what is taking place in Gaza have no evidence to support it. Clearly, not everything requires the type of evidence that we offer but there should be some reason why people are exerting effort and putting their time, their very lives, into something. From our work though, neither naming/shaming, economic sanctions, signing of international agreements, military intervention or other standard policy options should be pursued because they are not going to stop what is taking place. What should be undertaken, however, is a concerted effort to remove the leadership that thought of, ordered and implemented the human rights violations that people are focused on stopping. Now, such a policy seems like it would be problematic as it involves engaging in an effort to interfere with a foreign nation but the United States has had a long history of doing this type of thing. There is some humanitarian legal and moral precedent for taken such action like that articulated within the Right to Protect which requires the international community to step in when individual governments have decided to kill those under their care and not stop when asked to.

But if we, as Americans, are not allowed to discuss what is going on in the world and stand up for the protection of human life wherever it is threatened (with attempts to criminalize discussion of governments who violate human rights), then this hinders our ability to act upon as well as improve that world. Accordingly, there is no government (including our own) that should be above scrutiny and discussion. As far back as Hobbes (or even further) it was been clear that governments can have a privileged position in the international system until they violate their fundamental covenant to protect those within their jurisdiction. Once a government (any government) violates that covenant, then all bets are off regarding deference - this are theoretical, philosophical, legal and political reasons for following this course of action. Viewed as a violator, the rogue, excessively violent, illegitimate governments in question should not be given the courtesies extended to those governments who have not decided to kill those within their care. In fact these violators are expected to be targeted by individuals, governments and institutions the world over until the state-sponsored activity identified as unacceptable has ended. This is the call. This is the way.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed