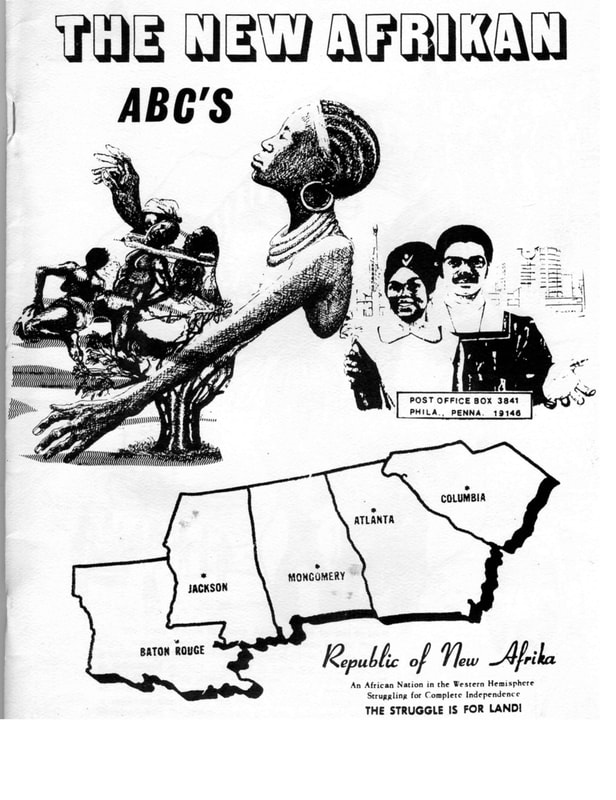

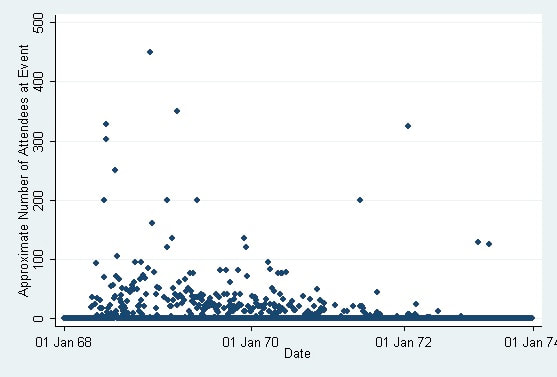

Almost four years ago, my book about the Republic of New Africa (RNA) came out entitled "How Social Movements Die: Repression and Demobilization of the Republic of New Africa. In the book, I attempted to strike a balance between theory and social science versus simply telling the story of the RNA. Unfortunately, I had to leave a lot of information out of the book and some of the details that were otherwise fascinating were eliminated. In this series, I revisit the archive and present the material 50 years later. Apologies for not being able to continue this piece for a while but life interfered. Enjoy. I will try to work my way backwards from this event as well as forwards.

“A is for Africa”: Social Movements and Framing Resistance in the Republic of New Africa

Core Framing Tasks

The RNA

- We, the Black People in America, in consequence of arriving at a knowledge of ourselves as a people with dignity, long deprived of that knowledge as a consequence of revolting with every decimal of our collective and individual beings against the oppression that for three hundred years has destroyed and broken and warped the bodies and minds and spirits of our people in America, in consequence of our raging desire to be free of this oppression, to destroy this oppression wherever it assaults mankind in the world, and in consequence of our inextinquishable determination to go a different way, to build a new and better society in a new and better world do hereby declare ourselves forever free and independent of the jurisdiction of the United States of America and the obligations which that country’s unilateral decision to make our ancestors and ourselves paper-citizens placed upon us.

- We claim no rights from the United States of America other than those rights belonging to human beings anywhere in the world, and these include the right to damages, reparations, due us for the grievous injuries sustained by our ancestors and ourselves by reason of United States lawlessness.

- Ours is a revolution against oppression --- our own oppression and that of all people in the world. And it is a revolution for a better life, a better station for mankind, a surer harmony with the forces of life in the universe (Republic of New Africa 1968a).

The core of the effort proposed was a somewhat radical reflection on the Duboisian paradox of African-American double-consciousness. The RNA simply suggested that blacks consider the long historical treatment at the hand of whites, since they were in the country in general as well as since they started to try changing their situation through the civil rights movement in particular. And, viewing this history, the Republic asked them to choose: stay in the US or leave and start the Republic of New Afrika. From the RNA’s perspective, the answer was clear: from the way blacks were treated, whites did not want them in the US. They never had and they never would. In response, they suggested that African-Amerikans should leave and make a better world. By adopting this position, many viewed the RNA as idealists, utopians or distopians – depending upon ones view of the imagined community that would result (a version of afro-socialism). But in certain respects, the RNA was probably one of the more realistic of the many groups that emerged during the period. The RNA’s realism was found in their sober analysis of the situation which emerged from viewing American society not as it should or could be but as they believed it was – segregated, unequal and at times quite violent.

This was a hard message to take for African Americans because it compelled a particular understanding and led to a particular solution. The harshness was slightly muted however by their reminding blacks that in many respects, they were already in the Republic. As they stated in their publication “Now We Have a Nation” (Republic of New Africa 1968b: 4):

- Though our people have struggled for 100 years to change the American Nation and become a part of it, we have failed to become a part of it – we still live separately, go to school and church separately, socialize separately, and act and react separately (and differently). And there is no real hope now that we can change America, because white people, who are in the majority, do not really wantAmerica changed. (Emphasis in original).

In a sense, the RNA suggested that blacks simply take a small but necessary step to complete what racism and hatred had already began: create a nation and secede from the US. How did they go about doing this? I address this below.

The New Afrikan A, B, C’s

Diagnosis. As conceived, the essence of any social movement diagnosis is detail – laying out the injustice (e.g., Benford and Hunt 1992). The movement must make it clear who did what to whom, why, when and how. At the same time, the social movement organization identifying the problem to be rallied around and mobilized against (i.e., problem identification and the locus of attribution) cannot seemingly overwhelm the recipient of this message with too much detail so as to make it appear that the problem is insurmountable. There is thus a delicate balance that must be maintained.

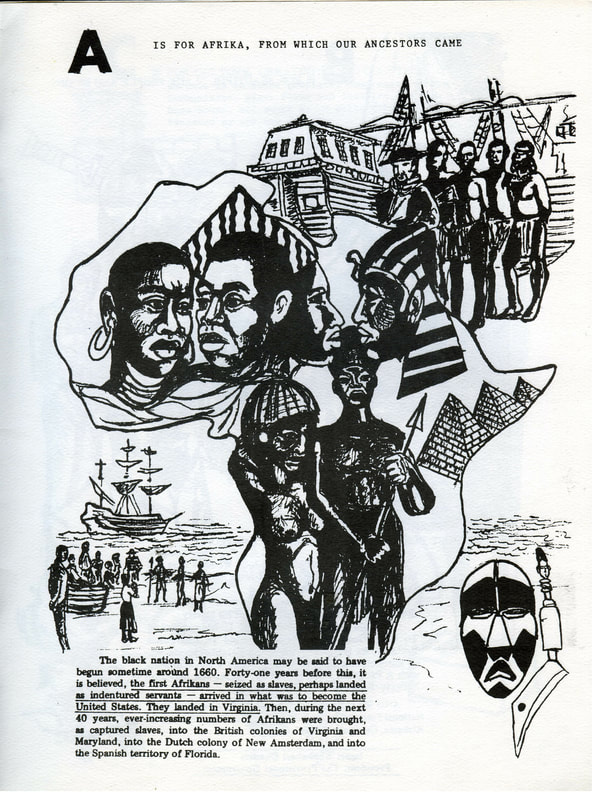

The RNA was clearly aware of this balance as they begin their book with “A is for Africa, from which our ancestors came” (Figure 1 shown above).

The image is a bold mélange with the top showing four Africans with their arms behind their backs and one white person – a slaver (with rifle under arm), marching them forward to some destination. All stand in front of a ship, which, from the angle, appears to be docked behind them. Immediately below this and taking up the majority of the page are depictions from Africa. Here, there are pharaoh looking individuals at the top – a male as well as a female, likely signifying nobility (literally overlaying the Nile valley where this civilization existed), pyramids lay over East Africa likely signifying intelligence, there is couple to the west looking past one another but in clearly observable African garb (i.e., large earrings and perhaps a series of neck rings) and there are more traditional looking Africans with spears, some sort of hats and bare-breasted. Below Africa to the left, the slave ship is off-shore, communicating that they have left the continent or are about to. A smaller ship, a white sailor and some Africans appear to stand on the beach. It is not exactly clear what they are doing but the ship sitting ominously in the background as well as knowledge about what transpired provides the meaning. Below Africa to the left are a mask and some tools (something that appears on every single page). In case the images are not clear, the following text is provided at the bottom of the page:

- The black nation in North America may be said to have begun sometime around 1660. Forty-one years before this, it is believed, the first Afrikans – seized as slaves, perhaps landed as indentured servants – arrived in what was to become the United States. They landed in Virginia. Then, during the next 40 years, ever-increasing numbers of Africans were brought, as captured slaves, into the British colonies of Virginia and Maryland, into the Dutch colony of New Amsterdam, and into the Spanish territory of Florida.

The message itself is thus fairly straightforward: theft and enslavement are the problems. The guilty are identified by image in the pictures and by deed in the text. They are not named or mentioned by race. Indeed, the references to them are somewhat vague (they are known by sight alone). While the victimized, the aggrieved and the potentially mobilized are shown in shackles (i.e., the condition that is in need of repair), the majority of the images are positive. =Indeed, they are depicted as something worthy of attention as well as returning to: Africa. Another interesting element concerns the number of blacks relative to the number of whites that are shown. Although the Africans are in bondage and whites have weapons, there are numerically more Africans in every scene. This appears to communicate that on some level blacks would likely have proven victorious, if they were willing to struggle against the slavers – en masse. Such a theme recurs throughout the children’s book: whites never outnumber blacks.

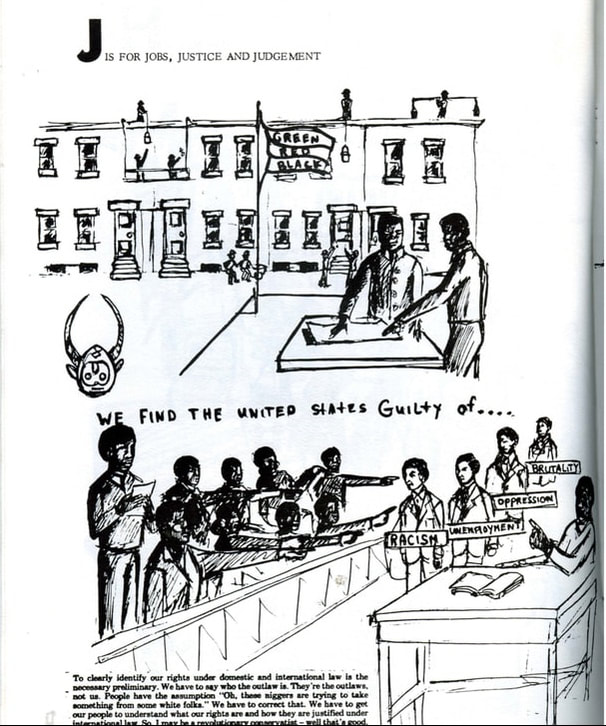

The themes identified above are broadly consistent with other characterizations in the book. For example, in “J is for Jobs, Justice and Judgement,” four white men in suits are in court charged with racism, unemployment, oppression and brutality. The jury is all composed of blacks (at least 9 shown) and the person seemingly presiding over the court (although they sit below the four whites) is also black. All of this takes place below an image of a series of row houses being built by and presumably for African Amerikans, under the red, black and green flag of the RNA. A little African icon sits to the left. The message: a new nation is being built; one complete with housing, employment and true justice where whites pay for what they have done.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed