After several weeks of reparations and negotiation, we met Innocent at the café – he was a member of an organization that advocated for those victimized during the violence. Innocent made an amazing impression. He was intense, soft spoken, present and skeptical. Our conversation started as many did with translations of introductions, then it was revealed that he spoke English. As many Rwandans, he did not think he spoke well enough and thus preferred not to but upon hearing him, it was clear he spoke better English than most Americans.

Innocent gave us “the” history lesson about how everything got to this point. He discussed the structure of the ancient kingdom with their fluid conception of Handbags and Teabags, the degree of formalism introduced by the Belgians – essentially freezing the socio-ethnic divisions, the discrimination of the Teabag minority against the majority Handbag and then the violence as well as discrimination against the majority Handbags against the Teabag minority. This was done with alarming speed as if he had done this a hundred times – which of course he probably had.

All this was background. His interest lay in telling us what happened after the killing stopped.

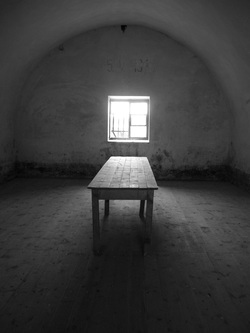

What he described was the growth of a survivors network: first, the victims of one massacre came together in a church, others in a school, others in someone’s house – all began to come back together. In these cells individuals attempted to recapture their lives: healing, talking, helping each other find food, shelter, information, peace, pieces.

After a while (over the course of a year or so) an initiative was made to bring all of the cells together and the organization that was formed out of this effort was called Ibuka – a Non Governmental Organization which represented all of the Tutsi victims.

The story of the organization was told matter-a-factly with no emotion or deviation. Interrupted by a question or statement, Innocent just continued. It was clear that we were meant to hear everything. It was clear that he was meant to tell us this, in the way that he told it. He assumed that we knew nothing about his country or that, if we did, we knew the wrong stuff. When he was finished, we sat there exhausted; yet, somewhat clearer for the journey.

Innocent’s position/role in the organization was complex. He was a lawyer by training and wanted to bring justice to those who had suffered. This was not some abstract thing for Innocent. He knew who killed his wife, child and father. The story he recounted for us was detailed but told in the same tone used to explain Rwandan history – factual, clear, direct from the soul but without affect. I didn’t expect him to cry or anything. I was probably teary-eyed enough for everyone in the bar. I did expect something. He gave nothing.

He would make the guilty pay but he wanted to use the law to do it. Al and I were from a society that would have respected this position but somehow we didn’t understand what Innocent had in mind. Here, we rely upon the law and police because we generally don’t know who did the crime. If we knew, I always thought, then we might be interested in/willing to address it ourselves. Despite all of our differences, Al agreed.

Innocent then went on to argue that if Rwandans took this path, they would never advance. Al and I sat humbled. Rwandans constantly put you in your place; somewhere that was not quite where you thought it was but clearly not where they were.

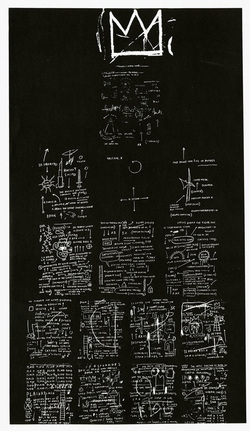

Innocent was not quite done. He did not believe in the system that had been created to find, evaluate and judge the accused – this was especially the case for lower-level offenders who were being tried in informal community processes called Gacaca (“Justice in the Grass”). He identified that the judges were trained for trials in a matter of weeks. They were frequently part of the same group that did the killings. There were no court recorders and thus people could lie; all things were done in the open – in the grass, and anonymity was absent. There was little communication between courts and thus the fact-checking as well as inappropriate behavior was near impossible to catch.

What was one to do in this situation? Collect information, eat, sleep, try to find meaningful work, interact with the friends as well as family that remain and wait. Wait for justice. Wait for peace. Wait for an opportunity. The smallest things in life frequently provide the greatest clues for why to continue living it.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed